Jólakötturinn

or

The Legend of the Yule Cat

By Gunivortus Goos

© Gunivortus Goos

This article is the realization and completion of a project on my to-do list that has been waiting for at least two decades. During these years, information has been gradually and incidentally collected from various sources, which were used to write and offer this article.

I hope you enjoy it.

One of the things that makes Christmas in Iceland very different from most other Western countries is the absence of a Santa Claus: In his place they have 13 Yule Lads, their Troll parents and …. the Yule Cat.

Note: The Icelandic jólahátíð means Yuletide, which is often traslated as Christmas or Christmas time. In this article Yule is kept.

The story of the Yule Cat or, as it is called in Icelandic, Jolakotturinn, is said to have originated in the Middle Ages, although the oldest written versions of the story date from the 19th century. The lack of older sources for the Yule Cat is not saying much, however, as the sources for any form of popular culture in the past are quite limited.

The story goes that medieval employers rewarded their employees every Christmas for their hard work with new clothes and shoes. However, if you were lazy and were not rewarded with new clothes, the yule cat would come and eat you. A new twist to the story is that if you give someone new clothes, you will not be eaten. The story is clearly intended for children to encourage them to be productive and avoid laziness.

The legend of the Yule Cat is a Christmas story that is still celebrated and told to Icelandic children today. Every year, a large Yule Cat is erected in Laekjartorg Square in Reykjavik.

The Yule Cat is associated with a special group of supernatural beings which people who are somewhat informed about Norse mythology may recognize as being quite similar.

The central figure of this group is Grýla, who can be seen as a dark, twisted version of Santa Claus. In post-medieval Icelandic folklore, Grýla is a terrifying ogress or female troll who is the mother of the thirteen Yule Lads. She lives in the mountains of Iceland and her home is said to be a huge cave. She is by no means a kind mother to these boys, baking cookies and providing warmth and security, she is more like the Krampus (a demonic, terrifying figure from the Alps, possibly dating back to pre-Christian times and associated with St. Nicholas). It is said to be a cruel yuletide or Christmas monster that appears only at this time of year.

Every Christmas Eve, she comes from her mountains and, together with the Yule Cat, devours naughty children. The origin of Grýla, who is married to the troll Leppalúði, is almost as obscure as that of the Yule Cat, but is apparently rooted in the Middle Ages and even beyond. In the Sturlunga saga, the name Grýla is mentioned several times, although it seems to refer to a specific character rather than a species. In a þula (a kind of rhyming verse) to Snorri Sturluson’s (1179-1241) Skáldskaparmál (“Language of Poetry”), Grýla is mentioned along with other troll women. Although the term troll is extremely vague and does not represent a uniform species, there is agreement on certain characteristics of trolls. They are always ugly, inhumanly strong, lustful and cannibalistic. It is almost a literary trope in the sagas that the heroes are seduced by troll women and constantly discouraged from sleeping with them or sharing their food.

Some say she is just some kind of specter who enjoys scaring people. Other stories show her in a much darker form, where she hunts and catches children who have misbehaved. She finds them, puts them in her big bag, carries them to her cave in the mountains and boils them in a big cauldron before eating them.

In Iceland, she is also famous as the mother of the Yule Lads and has the Yule Cat as a pet.

Grýla was married before she met her current husband Leppalúði. Her first husband’s name was Boli with whom she had many children. Boli was also a cannibal, just like Leppalúði. When Boli died of old age, Grýla met Leppalúði.

Grýla was not old even though she had so many children, for a folklore story by Jón Árnason tells us that Grýla and Leppalúði had 20 children together, and that Grýla was 50 when she had Leppalúði’s last children, twins. The twins died while they were still in their cribs.

Grýla looks like a female devil. She has horns on her head, cloven hooves as feet and 15 tails! She has excellent hearing and can hear when children are naughty. Children in Iceland have been afraid of Grýla for generations and do everything they can to avoid ending up in her sack. Fortunately, Grýla cannot eat good, quiet children.

Grýlas also occur in the Faroe Islands and a closely related monster occurs in Ireland. It is closely related to the fear of hunger in the barren winter season: it is always hungry and threatens to kidnap the children, of course only the naughty ones. While the Yule-Lads have become milder in stories in recent centuries, Grýla has remained malevolent, keeping alive the old tradition of evil Christmas spirits. In old stories, she has many heads, eyes on the back of her head, a beard, fangs, a tail and hooves – in other words, a real monster in appearance as well.

Gryla was such a terrifying image to children that in the 18th century the Icelandic parliament passed a law in favor of children from being threatened with being devoured by Grýla. Instead, they were given rotten, stinking potatoes stuffed in their boots if they misbehaved.

Leppalúði, Grýla’s husband, is also a troll. He would not look as ugly as Grýla, but that is often doubted. Both are parents of 20 children, not to mention the Yule Lads.There are 13 such lads, but older counts exist that are higher. And there is a poem in Jón Árnason’s folklore collection that describes another 19 of Grýla’s children.

Leppalúði had an illegitimate son named Skröggur. He fathered this son with a girl whom Grýla nursed while she was sick and bedridden for a year. Leppalúði could not take care of Grýla and her large household, so he hired the girl Lúpa to do so. When Grýla was recovered from her illness, she became furious when she learned that Lúpa had a child by Leppalúði. Thereupon she expelled Lúpa and Skröggur from her home.

Leppalúði is actually described as a lazy troll who has no function other than to be Grýla’s husband and henchman. In fact, he is never mentioned or depicted unless he is hunting with Grýla.

The Yule Lads, a translation of the Icelandic “Jólasveinar” (also often called “Christmas Lads”), are the most famous offspring of this fearsome pair of trolls and are described as very mischievous and naughty. And who wouldn’t be if you were raised by two such fearsome trolls as Grýla and Leppalúði? Historically, the Yule Lads were much meaner and more wicked, but from the 18th century and especially in the 19th, they became markedly friendlier. An 18th century royal decree on religious practices and domestic discipline prohibited parents from reprimanding their children by frightening them with horror stories about monsters like the Yule Lads. These boys retained their old habits of mischief and theft, but their appearance changed. In old stories they were described as monsters that looked little like humans, but in the 19th century they took on human form.

The characteristics of the Yule Lads, reflected in their names, provide a further clue to their origins as a reminder that people should be mindful of the scarcity of food in winter. Sausages, smoked leg of lamb, skyr and milk can mysteriously disappear if not properly guarded. The yule boys were responsible for this.

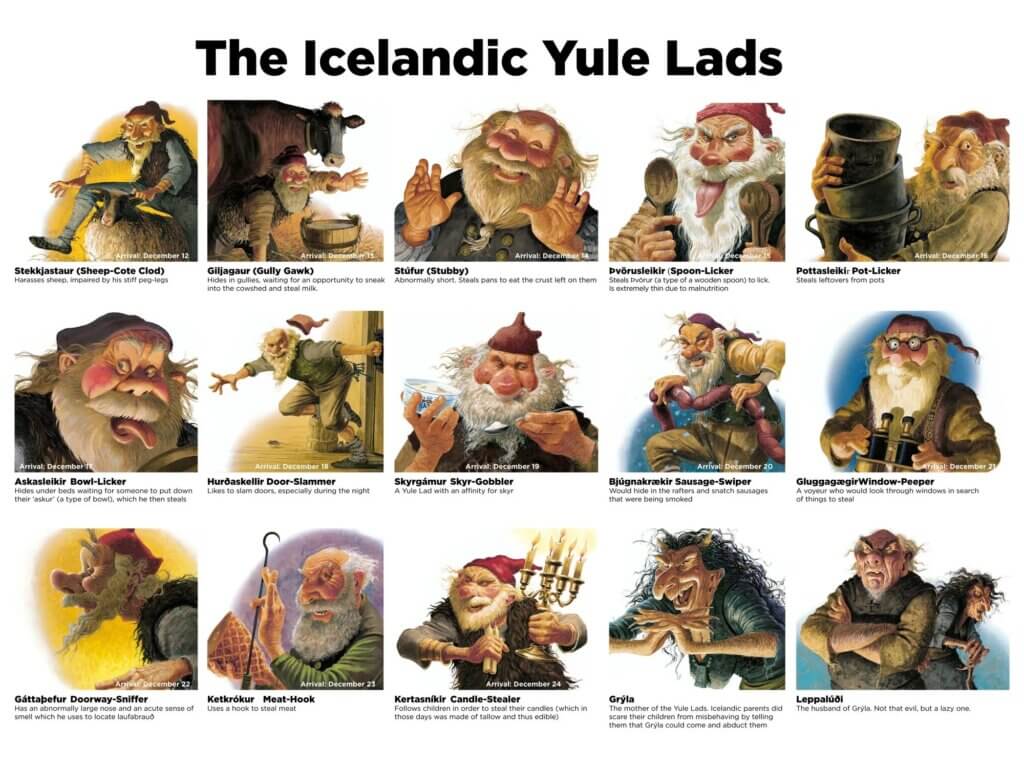

The individual Yule Lads are:

Sheep-Cote (Stekkjastaur) is the first Yule boy to arrive. He appears on Dec. 12 and returns home on the 25th. He has wooden legs and needs a walking stick to get out of the mountains. He is a rogue like his brothers and his job is to go to the outhouses, find the sheep and steal their milk.

Gully Gawk (Giljagaur) comes second on December 13 and returns home on the 26th. He comes down the mountain via the ravine. His specialty is to go into the barn and steal the cows’ milk. These days there is a beer called Giljagaur. I wonder if it tastes like milk?

Stubby (Stúfur) is the third Yule Lad. He comes on December 14 and goes home again on the 27th. He has nothing to offer except that he is small, very small. That is why he is the children’s favorite boy. Oh, and he grabs the frying pan from the kitchen and scrapes the burnt bits off the bottom, because those are his favorite bits. Every kitchen should have a Stubby to help clean the pans!

Spoon-Licker (Þvörusleikir) is the fourth, a tall and slender boy. He appears on Dec. 15 and returns home on Dec. 28. It is said that he used to like to suck his thumb. But now he grabs any cooking spoon in an instant and licks it clean. He may be crazy, but he is also endearing.

Pot Scraper (Pottaskefill) is the fifth. He appears on Dec. 16 and returns home on the 29th. He has a very long tongue and licks out cooking pots with great skill. His favorite is rice pudding. When the children run to the door to see who is coming to visit, he sneaks into the kitchen and in no time he has taken the pot and licked it clean.

Bowl-Licker (Askasleikir) is the sixth. He comes to town on the 17th of December. To get nutrition he licks the „askur“ bowl clean. Askur was a traditional food container that people used in the olden days. It was made from wood with a lid. When people had finished their meal they would usually place the askur under their bed where the dogs would lick it clean, only after this date Bowl-Licker would position himself under the bed waiting for his meal.

Door-Slammer (Hurðaskellir) is the 7th Icelandic Yule lad. He has the annoying habit of slamming every door he sees. If people wanted to take a nap in the afternoon darkness he would lurk around and then slam the door extra hard as they were falling asleep. Now isn‘t that just lovely?

Skyr-Gobbler (Skyrgámur), who is the eighth, loved his skyr. Back in the day the skyr was kept in the pantry in large wooden containers and would last for months. Skyr-Gobbler would sneak into the pantry, break the wooden lid and whisk up a handful of skyr and eat and eat until he almost exploded.

Sausage–Swiper (Bjúgnakrækir) is the ninth Yule Lad. He appears on December 20 and disappears again on January 2. He was fond of sausages, especially the “Bjúgu,” a large sausage made of lamb or horse meat that was smoked on the rafters. He would sit on the rafters and wait for the opportunity to grab the sausage and eat from them as much as possible.

Window-Peeper (Gluggagaegir), the tenth, is certainly the craftiest of the Yule Lads. His activity begins on Dec. 21 and is over again on Jan. 3. He sneaks up to people’s windows and peeks through them, especially at night. He is probably looking for things to steal later.

Doorway-Sniffer (Gattathefur), the 11th Yule Lad, appears on Dec. 22 and goes home again on Jan. 4. He has a huge nose and smells the scent of delicious Christmas foods such as lace bread and smoked lamb all the way to the mountains. Then he sniffs his way down to the farms, where he tries to grab a bite.

Meat-Hook (Ketkrókur), the 12th, is no ordinary Yule Lad who brings presents down the chimney to all the good children. No, he climbs onto the roof with his hook and with it angles a piece of smoked lamb hanging in the chimney. Roasted lamb is a traditional dish on Dec. 23. For him, as for the other Icelandic yule boys, the Christmas season is more about taking than giving. His acting begins on Dec. 23 and disappears again on Jan. 5.

Candle-Scraper (Kertasníkir) is the 13th and last Yule Lad. He arrives on Dec. 24 and returns home on Jan. 6. He mainly targets candles burning in the houses. He waits for the little children and tries to take the candles from them, which used to be very valuable. In earlier times were candles a common Christmas gift. Nowadays, however, children enjoy giving the candle thief a candle or two.

Except in December, the 13 sons of trolls almost never leave the troll cave. Only in December does Mother Grýla allow one after another to leave the cave to go from the mountains to the human settlements. Only when the last one returns to the mountains on January 6, does the Yule Cat also return. Then, when the last of the troll family has disappeared into the mountains on January 6 (Epiphany), a big bonfire is lit and fireworks are set off once more, just like on New Year’s Eve.

Although they had not inherited cannibalism from their mother, Icelandic trolls were still greatly feared by children because of their creepy and repulsive behavior. Even adults in Iceland largely believed in trolls before industrialization, so many were wary of whether there was any truth to the stories about these Yule Lads.

Although each Yule Lad had his own idiosyncrasies, they all had the same characteristics of trolls. They were huge, nasty, unintelligent creatures, as human-like as they were beastly, who could only act at night because the sun would turn them to stone during the day if they didn’t hide.

Back now to the Yule Cat ….

Grýla and Leppalúði owe the Yule or Christmas Cat, a horrible big cat that lurks on Christmas night and eats people who have not received clothes as Christmas presents. So you had better buy such Christmas presents if you don’t want the howler cat to eat you!

It is also known from old sources that it was considered particularly bad not to get new clothes for Christmas. The Yule Cat and its associated beliefs may have traveled from the Celtic world through the Shetlands and Norway to Iceland in a similar way to other better-documented traditions.

Although originally an oral folklore, the Yule Cat was made famous by a poem by the poet Jóhannes úr Kötlum (1899-1972), which describes a huge and very dangerous cat that roams the snowy landscape at Christmas time, catching people instead of mice. The translation of the original Icelandic text reads:

You know the Christmas cat

– that cat is very large.

We don’t know where he came from

nor where he has gone.

He opened his eyes widely

glowing both of them.

It was not for cowards

to look into them.

His hair sharp as needles

his back was high and bulgy

and claws on his hairy paw

were not a pretty sight.

Therefore the women competed

to rock and sow and spin

and knitted colorful clothes

or one Iittle sock.

For the cat could not come

and get the little children.

They had to get new clothes

from the grownups.

When Christmas eve was lighted

and the cat looked inside

the children stood straight and red-cheeked

with their presents.

He waved his strong tail,

he jumped, scratched and blew

and was either in the valley

or out on the headland.

He walked about, hungry and mean

in hurtfully cold Christmas snow

and kindled the hearts with fear

in every town.

If outside one heard a weak “meow”

then unluck was sure to happen.

All knew he hunted men

and didn’t want mice.

He followed the poorer people

who didn’t get any new clothing

near Christmas – and tried and lived

in poorest conditions.

From them he took at the same time

all their Christmas food

and ate them also if he could.

Therefore the women competed

to rock and sow

and spin and knitted colorful clothes

or one Iittle sock.

Some had gotten an apron

and some had got a new shoe

or anything that was needful.

But that was enough

For pussy should not eat no-one

who got some new piece of clothes.

He hissed with his ugly voice

and ran away.

If he still exists, I don’t know.

But for nothing would be his trip

if everybody would get next Christmas

some new rag.

You may want to keep it in mind

to help if there is need.

For somewhere there might be children

who get nothing at all. Perhaps that looking for those who suffer

from lack of plentiful lights

will give you a happy season

and Merry Christmas.

The singer Björk sang this in Icelandic in 1983

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Wk3EU8muMM

English translation found at https://genius.com/Genius-english-translations-bjork-jolakotturinn-english-translation-lyrics

While the 13 Yule boys return to the highlands one after another, the Yule Cat spends all the time between December 12 and January 6 at people’s residences, especially right after the holidays.

Like theYule Lads, this cat also is fond of children. But for a completely different reason: they taste so well!

That’s why you have to be careful not to get too close. Because anyone who didn’t get clothes for Christmas is an easy victim for the Jólakötturinn. That’s why Icelandic children always get clothes for Christmas – which is very practical in the cold winter months.

The earliest written mentions of the Yule Cat date back to the 19th century, but it seems to be closely related to the Scandinavian belief in the Christmas goat. According to the story, as mentioned earlier, the Yule Cat grabs and eats children who do not get new clothes for Christmas. This belief is probably related to the tradition of farmers giving their servants new clothes every Christmas. The Yule Cat is also probably linked to the pressure to get all the weaving and knitting work done before the holidays.

The story probably originated as an incentive to keep working. In Iceland, wool processing was one of the main activities and they wanted to give the workers an incentive to have the autumn wool processed before Christmas. Those who participated in the work would be rewarded with new clothes, but those who did not were left empty-handed and hunted by the monstrous cat.

These stories are based on Icelandic folklore that may go back many centuries. They have changed over the years, but they have scared people from generation to generation.

Fortunately, in recent decades people have realized that it is good to treat children and the poor kindly! As a result, the Yule Lads and Grýla have softened somewhat. The Yule Lads are now lumpy, stupid and funny instead of mischievous and evil, and Grýla no longer eats children because she is now vegan! <sic!

But the yule cat is still the same, he’ll still devour you if you don’t have at least one new piece of clothing gotten for Christmas.

The cat’s danger used to be used to persuade people to knit off their stockings or gloves for Christmas so that the Yule Cat would not come and get you. Nowadays, however, the cat is used in a different way, namely to convince children that the wool socks they got from Grandma for Christmas are a good thing because it has prevented them from being eaten by a scary giant cat!

Historians see some parallels to the Yule Cat in the variety of creatures that traditionally accompany St. Nicholas in many European countries. This is often suggested as the origin of the Scandinavian Christmas goat or julebukk. Originally, the goat probably represented the devil and is therefore closely related to the Alpine crampus. Like goats, cats, especially black cats, were also associated with the devil. There may be a direct connection to the duivekater, a Dutch Christmas bread, and the lussekatt, which is a Swedish pastry. There is a hypothesis that the Yule Cat has its origins in Catholic times, when Nicholas, the patron saint of travelers and fishermen was very popular in Iceland, as evidenced by the many churches dedicated to him.

Finally, a story …..

Grýla and Jólakötturinn – Yule Cat

By Heidi Herman-Kerr (posted at https://inlus.org)

Retold by Gunivortus

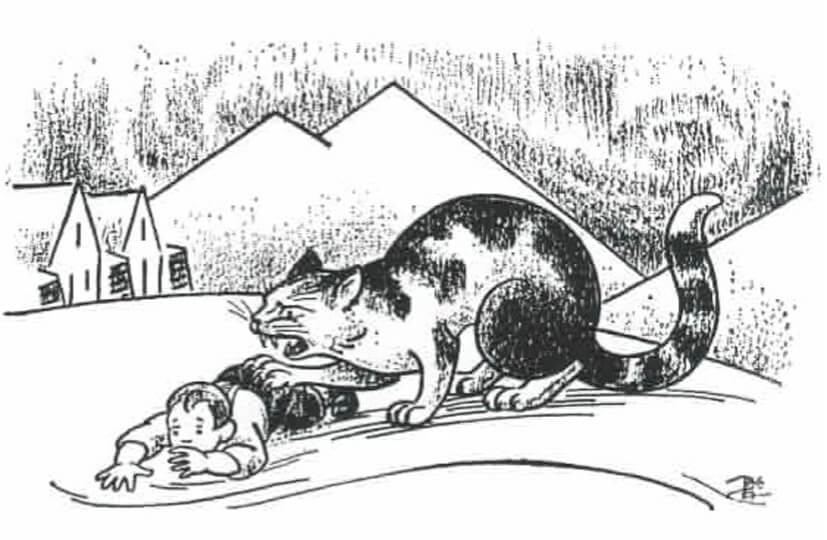

On a cold winter night, Gryla was on her way to fill her bag with naughty children. She was planning to invite visitors the next week and wanted to serve the guests a stew of naughty children.

Her pet walked beside her. The ugly beast had its own special way of tracking down the laziest children. Every fall he would sneak around waiting for the sheep to be sheared.

Gryla always sent him out to steal wool so she wouldn’t have to shear her own sheep. Gryla weaved many clothes with magic protective spells and needed a lot of wool. The cat looked out for unguarded bags of wool and stole as much as she could. She realized that anyone who helped shear or turned the wool into yarn or fabric would be rewarded with new clothes just before Christmas. That’s why Gryla’s cat liked to go looking for the children who didn’t get new clothes at Christmas because they had been too lazy. All he had to do around Christmas was look for those who wore old clothes. That is why he soon became known as Jólakötturinn (yola-cut-ter-rin), the Yule Cat.

That winter night, Gryla and the Yule Cat had visited the homes of two lazy children, stealing them from their beds and putting them in the sack that Gryla carried over her shoulder. She was tired and decided to collect just one more tonight, which then were enough to make a good stew for her guest dinner. They trudged on and soon reached the small house at the foot of the mountain. Jólakötturinn jumped up onto the peat roof and then down into the wooden smoke hole. He jumped onto the table in the house and nudged the window open with his nose so that Gryla could reach in.

The cat jumped outside as Gryla reached for the sleeping child and picked her up with one long, bony hand. The little girl’s eyes flew open, and she knew immediately that it was the terrible troll woman Gryla who had come to kidnap her. Before she could utter a warning and wake the household, Gryla had dragged her through the window and run down the street, clutching the little girl under her arm. Her long troll legs took giant strides, and in no time they were several miles from the farmhouse.

That concludes this article about the Yule Cat.

If you would like to find out more about this cat and the household to which she belongs, simply use the keywords for a web search.

Two audio links:

GRYLA – a seasonal Icelandic folk tale

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vWqCswodarQ

Hear the Yule Cat:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zdk5MeKmMvw