The Legend of Blenda

The Swedish Blodberget—the mountain of blood—owes its name to an old legend about a woman named Blånda, Blända or Blenda. Peter Rudebeck (1660–1710), a former owner of the ironworks in Huseby (today a stately, castle-like manor house with magnificent gardens and historic grounds where in the easrly days was a small village), wrote down the legend and told it everywhere.

It is said to have happened a long time ago when Danish troops attacked the area around Åsnen (a lake in Småland, southern Sweden).

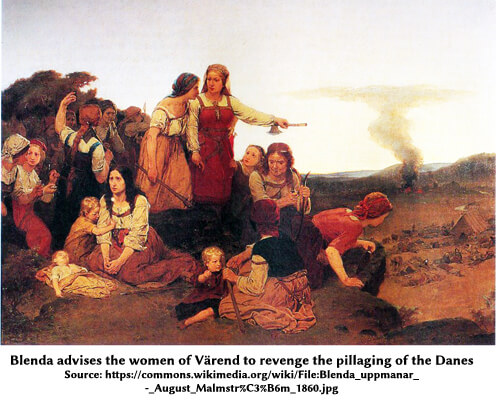

Thereupon, Blenda called on the women of the region to resist and gathered them at a place called Skäggalösa. The corresponding village on the eastern shore of the Skatelövsfjord still bears this name today (the Skatelövsfjord is a bay north of Lake Åsnen in the municipality of Alvesta).

From that gathering place the women’s group moved further north.

At Dansjön, a lake in the municipality of Alvesta in Småland, the Danes defeated a small local army and wreaked havoc without much resistance, as most of the men in the area were on a military campaign—legend has it that during the reign of Alle (Anglo-Saxon: Ælla), King of the Geats, a significant event occurred when the king himself led an assault on Norway with the Geats. King Alle not only gathered the West Geats, but also the South Geats (or Riding Geats) of Småland, resulting in a mass exodus of men to Norway and leaving the region vulnerable to attacks.

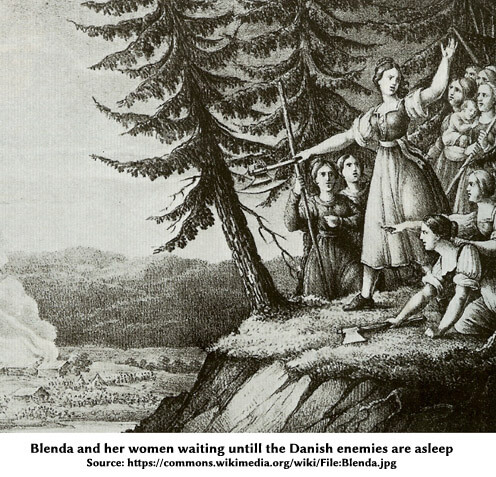

When Blenda and the women from the village of Värend arrived, they told the Danes how much they were impressed with the Danish men and they invited them to a feast on the Bråvalla heath and began to treat the Danish army to food and drink. The soldiers enjoyed plenty of beer and mead and eventually fell asleep. Shortly afterward, the women came with sickles and cut the throats of every Dane.

After the bloodbath, the women washed themselves at a spot by the lake, which was therefore called Blotviken—Bay of Blood. The hill at this spot was given the name Blodberget—Blood Mountain. In the past, fertility festivals were also held on Blodberget to pay homage to the old gods.

Blenda was awarded a golden emblem for her deed. The emblem is still worn today in the red sash, which is part of the Värend costume. The women of Värend were also promised the same inheritance rights as the men. This was confirmed by medieval deeds of inheritance. They were also given the right to go to church on their wedding day in full battle dress with drums and kettledrums.

Towards the end of the 17th century, however, King Charles XI issued a new church law with modified marriage and inheritance rights. At this time, Peter Rudebeck approached Erik Dahlberg, a friend of the king, with a request to remind the regent of the Blända legend. In this way, the hereditary rights of the Värend women were preserved for the future.

Some Swedish researchers are of the opinion that the legend was invented at the end of the 17th century by the regimental quartermaster Petter Rudebeck. However, it was accepted by serious Swedish historical research for a long time. The story was quickly spread in a series of prints, and when Olof von Dalin included it in his historical works, it even gained historical authority.

Critical scholars believe that Rudebeck modeled the story on the ancient tale of Philotis, a slave girl who similarly managed to hold off an army from the city of Fidenae that had surrounded Rome when the city was weakened by the Gallic invasion in 387 BC.

The Philotis story (it was also called Tutola and Tutela):

After the Romans suffered a defeat against the Gauls during the Latin Wars in 387 BC, they found themselves in great difficulties. The Latins took advantage of this situation. A Roman army led by Camillus pursued the Gauls to avenge the defeat. Those left behind in the city were too weak to defend the city against further attacks. The Latins under Livius Postumius seized this opportunity and laid siege to the city gates. Through a herald, they demanded a larger number of marriages between the two peoples in order to establish new connections, similar to what had already happened between the Romans and Sabines. The Latins therefore demanded the surrender of a larger number of Roman virgins and widows as a guarantee of peace and friendship between the two peoples. However, the Romans agreed to Tutola’s proposal and sent maids and slaves dressed as Roman matrons in place of the Roman women. After this plan was successfully implemented, Tutola gave the Romans a sign in the form of a signal fire from a fig tree, far enough away from the Latins’ camp but placed so that the Romans could see it to show that the Latins were asleep. In the meantime, the supposed Romans had stolen the swords of the sleeping Latins. Now the remaining Roman men attacked the Latins, defeated them and killed most of them.

Several attempts have been made to prove the historical plausibility of this Blenda legend. Johan Stiernhöök wanted to date the events to the 7th century. Olof von Dalin assumed that the battle took place in the 1270s during an attack by Erik Klipping on Småland. Sven Lagerbring assigned the event with reservations to King Sven Grates’ invasion of Sweden in the 1150s; some later authors assumed that it took place at the time of Sigurd Jorsalafarare’s attack on Kalmar in 1123 or during the fighting shortly before the meeting of the three kings at Konungahälla in 1101.

Probably the origin of the legend most respected by critics was presented by Carl Johan Schlyter, who believed that the story was invented to explain the introduction of equal inheritance rights in Värend.

In any case, Blenda’s name was first mentioned in writing when equal inheritance rights were to be protected at the Law Commission in the drafts of the 1680s and 1690s. They were also mentioned as arguments against the new church law’s ban on the use of drums at weddings.

Gunivortus

Download this article as a PDF