By Gunivortus Goos, Sept. 2025

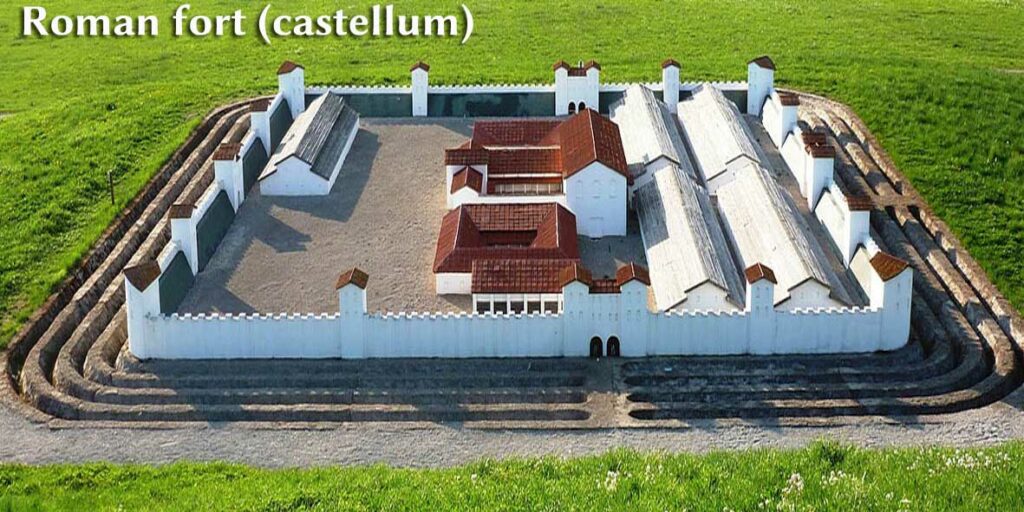

In the year 28 CE, the Frisians revolted after Olennius, the newly appointed Roman governor, significantly increased taxes and acted harshly against the unrest that ensued. The Frisians mobilized an army and attacked the Romans at the Castrum Flevum, which some historians locate near the current town of Velsen (see red dot on the map below).

The Latin term ‘Castrum‘ was utilized to refer to military camps of varying sizes, including large forts, smaller fortifications, and temporary encampments. It served as a base for military operations or as a temporary location prior to battles. Notably, the permanent garrisons of these forts significantly contributed to the Romanization of the conquered territories due to their economic strength and the technological advancements that were previously unknown in many regions.

After intense fighting, the defenders barely managed to repel the Frisians. Lucius Apronius, the commander of the Roman border army at the Lower Rhine, hastily sent reinforcements northward by boat. When this force, consisting of the Fifth Legion and auxiliary troops, arrived in the territory of the Frisians, these already had retreated towards the Baduhenna forest.

It remains unclear where this forest was located; it is generally accepted today that it was not far from the Castrum Flevum, possibly a one or two days’ walk away. It may have been a relatively water-rich or swampy forest situated in the area of present-day Kennemerland or West-Friesland. Based on this assumption, the forest would have been to the north of Flevum. More than a mere suspicion, it could have been such a marshy region located just behind the beach, where at that time there were almost no dunes to protect the land from the sea: Approximately 30 kilometers (ca. 18.6 miles) north of Flevum, there was such a place, to the west of present-day Alkmaar, where a forested brackish water area could have existed.

Flevum possessed a harbor and served as a base for Roman naval forces. It controlled a significant waterway, the northernmost outlet of the Rhine River, as well as an exit from Lake Flevo. The fort was likely constructed between the years 14 and 16 CE, indicating that it was intended to support the expeditions of the Roman general Germanicus in Germania.

Hence, the Frisian army likely advanced northward, subsequently followed by the Romans. A forward-deployed cavalry unit from the Cananefates, accompanied by infantry from other Germanic peoples, caught up with the Frisians but was defeated by these. Additionally, a cavalry unit from the legion, which rushed to provide assistance, was also dealt with. Following this, the Frisians reached the Baduhenna forest, which they were probably well acquainted with. Consequently, the Frisians held an advantage over the Romans; they were familiar with the navigable paths within the forest and the waterlogged surroundings, and unlike the Romans, they were lightly armed, which allowed them to navigate the marshy terrain with greater ease. The battle in the forest in the year 28 CE resulted in a resounding victory for the Frisii.

The fort Flevum was subsequently abandoned, and the survivors retreated to the region south of the Rhine. The fallen Roman soldiers, including many high-ranking officers, were left on the battlefield. Emperor Tiberius did not send a new punitive expedition to the area, allowing the Friesians to regain their freedom. Later, in 47, the general Corbulo reestablished Roman authority there at the behest of Emperor Caligula, but he was later ordered by Emperor Claudius to withdraw behind the Rhine.

According to Tacitus in his Annals, in 28 CE many Roman soldiers died in a heavy battle in the Dutch province of North Holland, located in the northwest of the Netherlands. Because that territory was Frisian, this goddess Baduhenna is assumed to have been worshiped by the Frisian people.

The chapters 72 and 73 of book 4 of Tacitus’ Annals narrate what happened:

That same year the Frisii, a nation beyond the Rhine, cast off peace, more because of our rapacity than from their impatience of subjection. Drusus had imposed on them a moderate tribute, suitable to their limited resources, the furnishing of ox hides for military purposes. No one ever severely scrutinized the size or thickness till Olennius, a first-rank centurion, appointed to govern the Frisii, selected hides of wild bulls as the standard according to which they were to be supplied. This would have been hard for any nation, and it was the less tolerable to the Germanics, whose forests abound in huge beasts, while their home cattle are undersized. First it was their herds, next their lands, last, the persons of their wives and children, which they gave up to bondage. Then came angry remonstrances, and when they received no relief, they sought a remedy in war. The soldiers appointed to collect the tribute were seized and gibbeted. Olennius anticipated their fury by flight, and found refuge in a fortress, named Flevum, where a by no means contemptible force of Romans and allies kept guard over the shores of the ocean. As soon as this was known to Lucius Apronius, propraetor of Lower Germany, he summoned from the Upper province the legionary veterans, as well as some picked auxiliary infantry and cavalry. Instantly conveying both armies down the Rhine, he threw them on the Frisii, raising at once the siege of the fortress and dispersing the rebels in defence of their own possessions. Next, he began constructing solid roads and bridges over the neighbouring estuaries for the passage of his heavy troops, and meanwhile having found a ford, he ordered the cavalry of the Canninefates, with all the German infantry which served with us, to take the enemy in the rear. Already in battle array, they were beating back our auxiliary horse as well as that of the legions sent to support them, when three light cohorts, then two more, and after a while the entire cavalry were sent to the attack. They were strong enough, had they charged altogether, but coming up, as they did, at intervals, they did not give fresh courage to the repulsed troops and were themselves carried away in the panic of the fugitives. Apronius entrusted the rest of the auxiliaries to Cethegus Labeo, the commander of the fifth legion, but he too, finding his men’s position critical and being in extreme peril, sent messages imploring the whole strength of the legions. The soldiers of the fifth sprang forward, drove back the enemy in a fierce encounter, and saved our cohorts and cavalry, who were exhausted by their wounds. But the Roman general did not attempt vengeance or even bury the dead, although many tribunes, prefects, and first-rank centurions had fallen. Soon afterwards it was ascertained from deserters that nine hundred Romans had been cut to pieces in a wood called Baduhenna’s forest, after prolonging the fight to the next day, and that another body of four hundred, which had taken possession of the house of one Cruptorix, once a soldier in our pay, fearing betrayal, had perished by mutual slaughter.

Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb translation

Tacitus conveys the notion, through his choice of words, that in contrast to the highly stylized Roman groves, the Germanic groves were perceived as untamed areas of their forests, possibly even associated with warfare.

As to the meaning of the name of this goddess … In the initial segment of the name “Baduhenna,” the Germanic *badwa-: ‘battle, combat’ is identifiable. The latter segment ‘-henna‘ has been linked to the Germanic *henk-, Gothic fra-hintan, and Old High German heri-hunda, all of which refer to ‘war booty, war loot’. When considered collectively, the name and domain of Baduhenna can be interpreted as: ‘She who acquires booty through victorious combat’. For her devotees, she represents a goddess who fulfills the aspirations of her (warrior-)worshipers.

In another explanation, the element -henna is associated with Matronae (Mother Goddesses), as forms such as -(h)enae are found there. In Latin, the name is written by Tacitus as: Baduhennae. However, this explanation has the problem that almost all of these names of mother goddesses are spelled with one “n”—such as Albihenae, Almaviahenae, Berguiahenae, Gesahenae, and more.

There is even a researcher who reconstructs the name as Celtic, positing a borrowing stage from the Celtic Bodu(c)enna- = Battle Goddess.

In all that is written here and elsewhere about the goddess Baduhenna and the related battle between the Romans and the Frisians, we must not lose sight of the fact that the aforementioned section in Tacitus’ “Annals” is the sole source for this information. Everything beyond this point is merely interpretation, theory, speculation, guessing, and indeed, also fantasy.

To conclude, here is my song about this battle…