Gunivortus Goos

© Copyright Gunivortus Goos, 2024.

This article may be shared freely, commercial use is strictly prohibited

LISTEN to the text below (audio file not yet created)

Note: At the end of this article there’s a printable PDF offered for download.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

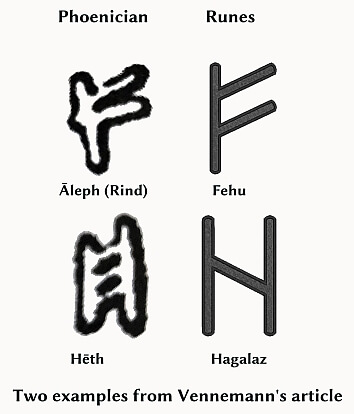

When Theo Vennemann published his long German article “Germanic runes and the Phenician alphabet” in 2006, my attention was drawn back to ancient Carthage since the stories about the Carthaginian commander Hannibal, who brought Rome into great distress in 216 BCE. A short quote from one of my books refers to the possible connection between the runes and Carthage:

“In 2006, the philologist Professor Theo Vennemann, called Nierfeld, published a new thesis in which the runic script is derived directly from the Phoenician alphabet, so, without borrowing from other Mediterranean writing systems. This refers to the western variant of this alphabet, as was used in the Empire of the Carthaginians in the 3rd Century BCE and earlier. Not only do remarkable peculiarities of the runes have an often plausible explanation, but this derivation also implies intensive contacts between Germanic Peoples and Phoenicians, which is supported by linguistic and cultural clues.”

The Carthaginian admiral and explorer Himilco (Himilkon, Phoenician Chimilkât) visited England and French Brittany in the late 6th or early 5th century BCE and probably also reached the North Sea coast of Denmark and Germany. In accordance with their usual practice, the Carthaginians established trading posts in all places where they encountered trade goods. They used their writing for administrative purposes, with their chosen Germanic trading partners also being initiated into these practices, for example to be able to document the goods transported to the settlement. The Phoenicians, whose influence was based on trade and seafaring, had numerous reasons for expanding northwards: Access to tin in English Cornwall and copper in Ireland was of great importance. Amber, honey, resin, salt and cliff fish were also important trade goods. As their society was based on slave labor, they may also have used northern Europe to partially cover their own needs for slaves as well as those of their trading partners in the Mediterranean.

According to Theo Vennemann’s theory, the runes originated from these contacts with Carthaginian writing. This topic will not be explored further here, but Vennemann’s article provided a bridge to my current interest in the history and myths of the Germanic tribes and Carthage.

It was therefore not surprising that when articles on the founding of Carthage came into my hands a few years later, I regarded them as ‘food’ for my interest in Carthage.

This was the beginning of research into Dido, the presumed founder of Carthage.

Even the ancient Greeks and Romans wrote about this woman and she is still the subject of publications today. This article is the result of my rich collection of information about her.

Probably the oldest source on Dido, who is also referred to as Alyssa, is a short paragraph in a writing by Timaeus of Tauromenium in Sicily (ca. 356ܺ-260 BCE). Although Timaeus’ writing has not survived, it is quoted by later writers or at least reproduced in their own words. According to Timaeus, Dido founded Carthage either in 814 or 813 BCE. A later source is the first-century historian Flavius Josephus, whose writings mention an Elissa (this was probably her Phoenician name and became Dido in Latin) who founded Carthage.

Josephus quotes from a list of Tyrian kings compiled by Menander of Ephesus (ca. 200 BCE) who ruled there from the 10th to the 9th century BCE. It mentions an Elissa, sister of King Pygmalion (Pumayyaton). And it is this woman who is said to have founded Carthage in the seventh year of this king’s reign. (Tyre was an ancient city on the coast of Lebanon, one of the earliest Phoenician metropolises; the city still exists today).

The short text by Timaeus has evolved over time from about ten lines to extensive works by many well-known writers and playwrights. Especially the famous epic poem “Aeneid” by Virgil with the chapter “Aeneas and Dido”, which deals with at least one fall from grace, two deaths and the destruction of an heirless city, has meant that many of its adaptations often show characteristics of classical tragedies. There are also other similarities in the ‘Didonic’ literature. Virgil’s version incorporates the classical dilemma between love and duty. This dilemma persists in all dramatizations and links the various works of the genre. The authors usually deal with this dilemma differently by adding new elements to the original story.

In Book 18 of his Latin work “Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus,” the Roman historian Justinus, likely from the 2nd or 3rd century, recounts the myth of Dido. The story goes like this, summarized:

In Tyre, a city “overflowing with wealth and people,” King Mutto, on his deathbed, passes the throne to his two children: son Pygmalion and daughter Elissa, a maiden of extraordinary beauty. However, the people only want Pygmalion to rule, leaving Elissa overlooked and married off to her uncle Acerbas, the priest of Hercules, who ranks just below the king and possesses immense riches. The greedy Pygmalion has Acerbas murdered for his wealth, but Acerbas had wisely buried his gold long before. Elissa, who has harbored hatred for her brother since childhood, finally devises a plan to escape. Using a clever trick, she secures ships and a crew; along with her treasure and some prominent citizens of the city, she flees westward, after making a sacrifice to the Hercules of Tyre.

Initially, the group arrives at an unnamed location in Cyprus, where the gods compel the local priest of Jupiter, along with his family, to join Elissa. This divine command is interpreted as a favorable omen for their undertaking. In Cyprus, Elissa captures virgins who, “according to Cypriot custom,” engage in prostitution on the beach prior to their marriages, and she marries them off to the men in her entourage. They then continue their journey, while back in their homeland of Tyre, Pygmalion is deterred from pursuing them by the pleas of his mother and the counsel of the gods. The “enthusiastic seers” warned the resentful brother that he would not escape punishment if he obstructed the establishment of a city of global significance.

Dido and her followers arrive in a bay in Africa, where the locals warmly welcome them to engage in trade. The well-known tale of the clever land purchase unfolds: Elissa acquires just enough land for her people, as much as a cowhide can cover, and promptly cuts the hide into strips to encompass a sizable area. This leads to the place being named “Byrsa,” which means fortress in Phoenician, and refers to the elevated old town of Carthage. Hoping for profitable exchanges, more and more people from the surrounding areas gather at the Tyrian camp; they settle on the Byrsa, forming a sort of town. The newcomers are greeted by their relatives from nearby Utica, who encourage them to establish a permanent settlement.

The local Africans also support the Tyrians’ stay, as they receive an annual tribute for the settlement site. While digging for the foundations, a bull’s head is discovered, interpreted as an omen that the city will be wealthy but unfree; thus, they dig elsewhere and find a horse’s head, seen as a sign of a powerful and warlike city. “And so,” concludes Justinus, “with everyone’s agreement, Carthage was founded.”

As a sidenote … Utica was a Phoenician colony located in North Africa, about 40 kilometers northwest of Carthage. This shows that the founders of Carthage weren’t the first Phoenicians to settle along the North African coast. Cities like Tyre, an unnamed coastal city in Cyprus, and the Gulf of Tunis were key stops on a well-known trade route that easily extended westward. It’s probably not a coincidence that Dido’s escape route followed the trade path of Phoenician merchants heading into the western Mediterranean.

However, the narrative of the fleeing-myth above is recounted in a distinctly different manner:

It is assumed that Pygmalion ascended to the throne at the tender age of eleven, a position he was entitled to as the sole heir of the late king. During Pygmalion’s early years, the chief priest Acherbas likely served as regent until the young king came of age. However, Acherbas sought to strengthen his own hold on power by marrying Elissa, the sister of the monarch. Upon reaching eighteen, Pygmalion took decisive action by executing Acherbas and exiling Elissa to eliminate any potential threat to his sovereignty.

Carthage has been established, but the tale of Dido is far from over.

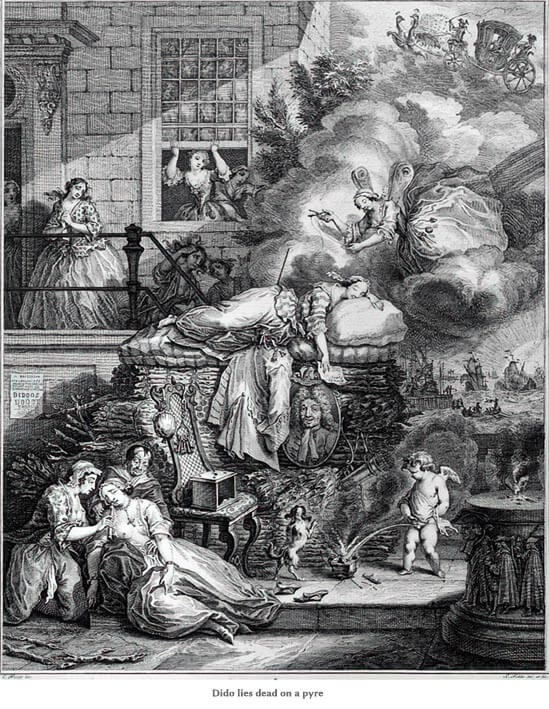

When Larbas (or Hiarbas), the ruler of the native Mauritanians, witnesses the rapid prosperity of the Carthaginians, he is consumed by jealousy. In a bid to claim a portion of their wealth, he seeks the hand of Dido from ten esteemed men of Carthage, threatening war if they refuse. To maintain peace, the nobles, fearing conflict, relent and urge the queen to guide the African barbarian towards a more civilized existence. The cunning Elissa plays along, requesting three months to consider while she constructs a massive pyre for animal sacrifices intended to appease the spirit of her slain husband. However, her true desire is to avoid sharing her life with a barbarian who lives like a wild beast. Ultimately, Dido herself approaches the pyre and plunges there her sword into her heart. After this self-sacrifice, Dido was elevated to the status of a goddess and worshiped for as long as Carthage existed.

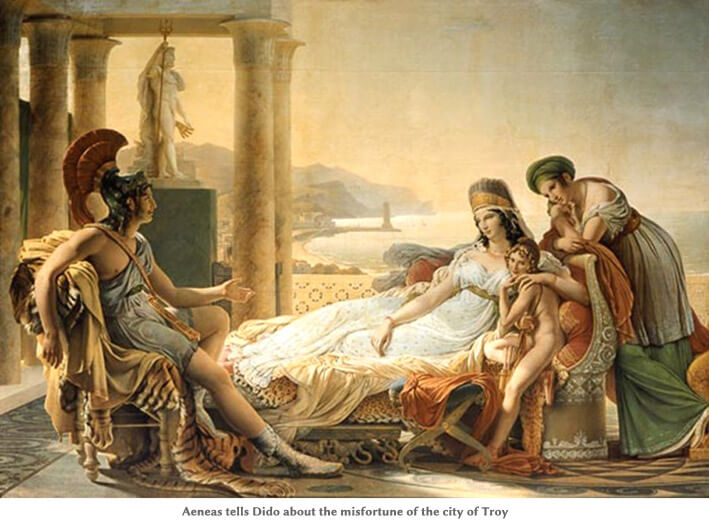

However, most people know Dido’s story from the above-mentioned “Aeneid” by the Roman poet Virgil (70-19 BCE). He worked on this epic from 29 BCE until his death. The Aeneid was based in particular on the Iliad and Odyssey, two Greek poems attributed to Homer. The story describes the mythical Aeneas’ escape from the city of Troy, which was in flames, and his subsequent adventurous travels, which ultimately led him to Latium (modern-day central Italy). There he is said to have disembarked near the site where Rome now is located and became the progenitor of the Romans. The entire Aeneid thus conveys an important founding myth of the Roman Empire, linking the origin of the Romans with the Trojans.

From this epic, here is a brief summary of the story of Aeneas and Dido:

On his way from Troy to Lavinium, Aeneas landed on the North African coast and met Dido there. He arrived at a time when Carthage was still in its infancy, yet he was astonished to find a city where he had expected only desert. There was even a temple to Juno and an amphitheater there, but neither had yet been completed. He wooed Dido, who resisted him until she was struck by an arrow from Cupid, but when he left her after some time to fulfill his destiny, Dido was devastated and committed suicide. Aeneas only saw her again in the underworld, which is described in Book VI of the Aeneid.

By the way… about Troy… Little is known about the depiction of historical events in the ancient Mediterranean, against the backdrop of which the myth of Dido-Elissa emerged and was gradually shaped in literature. The prehistory begins in the Levant around 1200 BCE In this decisive year, at the end of the Bronze Age, not only the eastern Mediterranean, but the entire European-pre-Asian region experienced a catastrophic upheaval: powerful empires that seemed to last for eternity collapsed like houses of cards, and wealthy, influential cities were ravaged by fire and destruction. Mycenae, Troy, the Hittite capital of Hattusha and the Syrian port city of Ugarit – all these places fell into ruins shortly after the transition from the 13th to the 12th century in 1200 BCE.

Back to the Aeneas-Dido myth … Although this myth by Virgil regarding a love affair between Dio and Aeneas is probably the best known, it is not possible for chronological reasons alone. If historicity plays a role here, Aeneas is said to have fought in the Trojan War. This war is usually dated to the 14th to 12th century BCE. If Carthage was founded from around 814 BCE, an encounter between the two is impossible. Well, Virgil was first and foremost a poet who incorporated historical events into his work as he pleased and adapted the chronological sequences to fit to his work.

Although Dido is a unique and fascinating figure, it remains unclear whether there actually was such a historical queen of Carthage. However, there is evidence that this could indeed have been the case. In 1894, a small gold pendant with a six-line inscription was found in a cemetery in Carthage dating from the 6th to 7th century. This mentions Pygmalion (Pummay) and gives a date of 814 BCE. This indicates that the founding dates of Carthage listed in historical documents could well be correct. Pygmalion could refer to the aforementioned king of Tyre from the 9th century BCE. Perhaps the pendant was part of the riches brought from Tyre.

Many historians and myth researchers of our time now have differing opinions on the mythological Dio. For example, Michael Grant claims in his “Roman Myths” from 1973 that Dido-Elissa was originally a Goddess and was transformed from a deity into a mortal (albeit still legendary) queen by a Greek writer sometime in the later fifth century BCE.

The story of Dido was and is a source of inspiration for various artists, as a few of the many examples testify:

Christopher Marlowe adapted the mythological material in his drama “Dido, Queen of Carthage”

William Shakespeare mentions Dido twelve times in his plays: four times in “The Tempest,” albeit in a single dialog, twice in “Titus Andronicus,” also in “Henry VI” Part 2, “Antony and Cleopatra,” “Hamlet,” “Romeo and Juliet,” “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” and, most famously, in “The Merchant of Venice” in the mutual courtship of Lorenzo and Jessica.

There are around 90 operas that deal with the tragic love between Dido and Aeneas. Particularly noteworthy are the settings by Johann Adolph Hasse as well as “Dido and Aeneas” by Henry Purcell and “Les Troyens” by Hector Berlioz

Numerous depictions of Dido can be found in European art history.

In the fifth edition of the computer game series “Sid Meier’s Civilization,” Carthage is represented under Dido as a playable civilization.

“Mount Dido” in Antarctica bears her name.

The British singer Florian Cloud de Bounevialle O’Malley Armstrong named herself after the legendary Queen Dido.

A final brief note regarding Carthage… In antiquity, Carthage served as the capital of a significant maritime and commercial empire bearing its name. The Romans referred to its inhabitants as “Punic,” a term derived from “Phoenicians.” Following the Roman conquest and subsequent destruction of Carthage in 146 BCE, the Carthaginian Empire was effectively dismantled and integrated into the Roman Empire. Nevertheless, during the period spanning the 6th to the 2nd centuries BCE, Carthage was recognized as a formidable independent power, with its vessels navigating extensive maritime routes. The Carthaginians established trading posts wherever they identified advantageous trade opportunities, likely extending to the coasts of present-day England, France, northern Germany, and southern Denmark. This leads us back to the initial premise of this article, which posits that the earliest runic scripts may have been influenced by Carthaginian writing systems. Thus, the narrative comes full circle.

Because this is a web article for my site “Boudicca’s Bard” (https://boudicca.de) I had to restrain myself from writing many more pages, for example about related texts from antiquity with quotations and Dido receptions from the Middle Ages onward.

For those who would like to read more about Dido and Carthage, I recommend the following brief overview of some sources. By no means all the sources that I have been collected or borrowed in recent years are listed, as such a list would at least triple the length of this article. However, a web search with “Dido” and related keywords or one of her other names provides a comprehensive overview of serious and less serious sites and printed media about her. Have fun with it!

Gunivortus, September 10, 2024

Overview of Sources

Anonymous, The Fourth Book of Virgil’s Aeneid: Being the Entire Episode of the Loves of Dido and Aeneas. Translated Into English Verse. to Which Are Added the Following Poems, Viz, Wilmington, 2018

Franklin Horn Atherton, Gertrude, Dido, Queen of Hearts, Wilmington, 2021

Goos, Gunivortus, Germanic Magic. Runes: Their History, Mythology and Use in Modern Magical Practice, Norderstedt, 2019

Grant, Michael, Roman Myths, London, 1973

Horsfall, Dr. N., Dido in the light of history. A paper read to the Virgil Society, November, 1973

Krahmalkov, Charles R., The Foundation of Carthage, 814 B.C. The Douïmès Pendant Inscription. In: Journal of Semitic Studies 26.2 (1981), pp. 177–91

Manuwald, Gesine, Dido: Concepts of a Literary Figure from Virgil to Purcell. Revised from a paper given to the Virgil Society on 9 October 2010, the digital repository for the Proceedings of the Virgil Society, vs28 – 2013 – 2014

Lepin, Ian Charles, Dido, Queen of Carthage, Independently published, 2017

Marlowe, Christopher, The Tragedy of Dido Queene of Carthage, Ahrensburg, 2011

Sommer, Michael, Elissas lange Reise. Migration, Interkulturalität und die Gründung Karthagos im Spiegel des Mythos, in: Almut-Barbara Renger and Isabel Toral-Niehoff (Eds.), Genealogie und Migrationsmythen im antiken Mittelmeerraum und auf der arabischen Halbinsel, Berlin: Edition Topoi, 2014, 157–176

Vallejo, Irene, Elyssa, Königin von Karthago, Zürich, 2024

Vennemann, genannt Nierfeld, Theo, Germanische Runen und phönizisches Alphabet, in: Sprachwissenschaft, Band 31, Heft 4, 2006, S. 367-429

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

https://www.thoughtco.com/dido-queen-of-carthage-116949

https://tunesienexplorer.de/2018/10/21/die-gruendungslegende-von-karthago-elissa-dido/

https://www.vergiliansociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/BiblVergilAeneis2014.pdf

http://digitalvirgil.co.uk/pvs/2013/part3.pdf

https://academic.oup.com/book/41588/chapter-abstract/353235441?redirectedFrom=fulltext (available at the ResearchGate.net site

http://digitalvirgil.co.uk/pvs/2013/part10.pdf

http://digitalvirgil.co.uk/pvs/2013/part5.pdf

http://mcllibrary.org/GoodWomen/dido.html

https://phoenician.org/elissa_dido_legend/

https://www.livius.org/sources/content/the-founding-of-carthage/

http://digitalvirgil.co.uk/2013/11/06/n-horsfall-dido-in-the-light-of-history/

https://gendergeschiedenis.nl/attachments/article/139/Historica%202016%20nummer%201.pdf

https://www.tertullian.org/fathers/justinus_04_books11to20.htm

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Picture 1: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Turner-Karthago-1815.jpg

Picture 2: Gunivortus Goos

Picture 3: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%C3%89n%C3%A9e_et_Didon,_Gu%C3%A9rin.jpg

Picture 4: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dido_ligt_dood_op_een_brandstapel_van_takken_en_huisraad._Links_op_de_voorgrond_is_een_vrouw_van_verdriet_onwel_geworden._Achter_de_brandstapel_kijken_vrouwen_op_de_stoep_voor_een_huis_versc,_NL-HlmNHA_1477_53013163.JPG?uselang=de