About Walburgis

Rewritten from “Illustrated Lexicon of Germanic Deities”, by Gunivortus Goos, Usingen, Germany, 2022, pp. 300, 301

Since the onset of the Renaissance in the 14th century, a significant amount of folklore and myths related to Walburgis have been documented. While it is possible to identify certain pagan elements within this extensive collection of narratives, a definitive distinction between Christian and pagan origins remains elusive. For centuries, ecclesiastical authorities at various levels have intervened, modifying and reinterpreting pre-existing lore, leading to the likelihood that much of the associated folklore was initially developed in relation to the Christian saint bearing the same name.

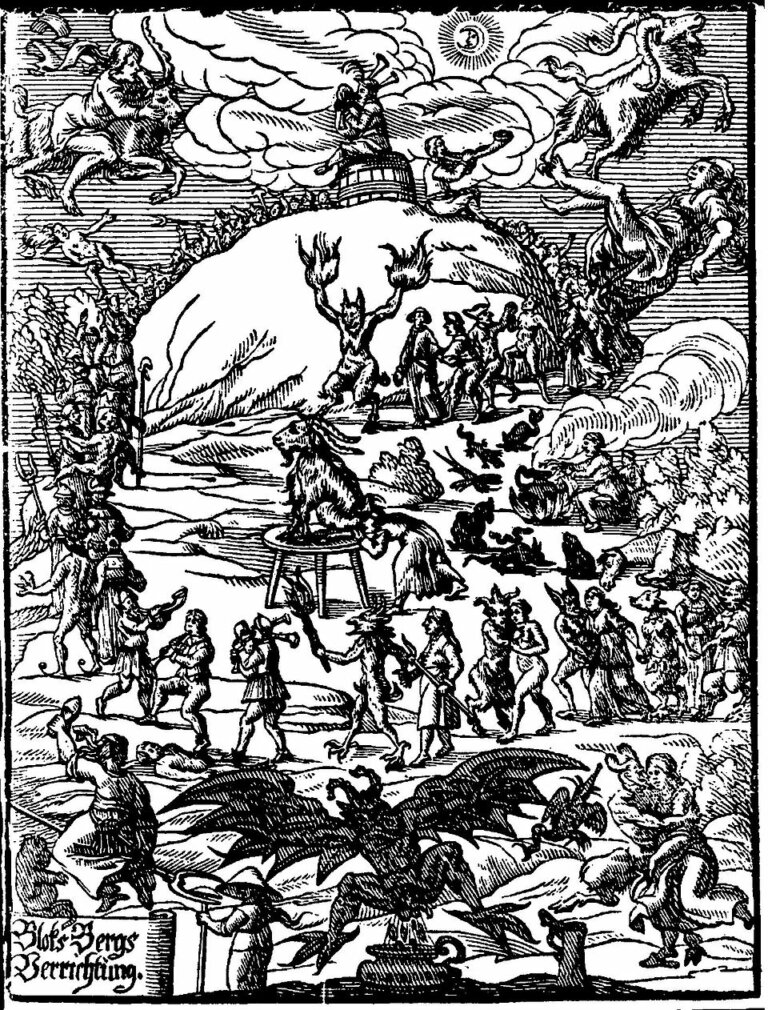

The figure of Walburgis likely embodies a pagan aspect, representing the divine leader of witches who convene on the Blocksberg (Brocken), a mountain located in the Harz low mountain range of Germany. Additionally, springtime traditions associated with Walburgis, such as the practice of riding around fields with new sprouts, are interpreted as originally stemming from a heathen fertility rite. The 1st of May was broadly recognized as a Pagan agricultural festival by the Franks and Saxons on the European mainland, yet it was later recontextualized within an ‘Act of Saints.’ Specifically, on this date in a chapel in Eichstätt, Germany, where relics of St. Walburga were housed, a clear, odorless oil was reported to miraculously drip through a wall. This oil was subsequently sold in small bottles as an elixir by the nuns, leading to the establishment of May 1st as a day dedicated to this saint.

In a pagan narrative, the goddess Walburga applies healing oil to a wounded warrior, while a parallel tale describes the healing of the sick through oil that drips from the breastbone relic of Saint Walburgis. It is believed that the pagan narrative represents the earliest account of Walburga, with subsequent stories emerging to supplant the ancient pagan traditions. Another myth that may have pagan origins recounts a farmer who, on the Night of Walpurgis, adorned his cow with green branches and a blanket, and after disrobing, led the cow outside to walk through the dew. Upon returning home, he squeezed the dew-soaked blanket into a bucket as if milking the cow. After his livestock consumed the dew-infused water, they yielded an abundant supply of milk throughout the year.

Walburga, a Christian figure from approximately 710 to 780, is believed to have been an Anglo-Saxon woman hailing from Wessex, likely of noble lineage and possibly related to the missionary Boniface. She undertook missionary work herself and served as the abbess of a nunnery in Heidenheim, a town situated east of Stuttgart, Germany. Canonized around 870, her relics were distributed among various churches and monasteries throughout Germany. Her final resting place is located in a Benedictine monastery in Eichstätt, a town south of Nürnberg in Bavaria. Following her canonization, a significant cult surrounding Walburga’s relics emerged, supported by the Benedictine order, bishops, and nobility, likely as a countermeasure to the enduring veneration of pagan deities still secretly honored by the populace. Additionally, this movement may have aimed to supplant a popular figure with one of noble heritage to reinforce the nobility’s claims to leadership. The Christianization of the Franks commenced on a large scale in the early 5th Century, with the Saxons following suit in the 8th Century.

This suggests that the goddess Walburga may have been recognized during that era due to the efforts to promote a Saint sharing her name. Based on various myths and traditions, Walburga is thought to have been an agricultural deity associated with happiness, beauty, and the love and fertility of married couples. In 19th Century literature, she is frequently compared to, and at times equated with, goddesses such as Freyja, Holle, Nerthus, and Venus, owing to her attributes and her influence on human affairs—similar to Holle, who is depicted in myths as rewarding or punishing individuals based on their actions. Nevertheless, these comparisons are largely speculative.

The etymology of the name Walburga remains ambiguous; however, it is acknowledged as having Germanic origins. The initial component may be linked to the Germanic terms *walda or *wala, which denote ‘power, ruler, or might’, or to *wala-, meaning ‘dead or battlefield’. An alternative interpretation, likely from a later period, suggests a relationship with the Old High German word wald, meaning ‘woodlands’. The latter part of the name is associated with the Germanic *burg, meaning ‘castle’, and *berga, which signifies ‘shelter’. Collectively, these elements may allude to a formidable goddess who provides protection.

Contemporary Celtic-oriented pagans in Germany and several other nations, who observe Beltane—the Gaelic May Day festival on May 1st—have adopted the term Walpurgis for their festivities. This has led to a misinterpretation of the Germanic goddess of the same name as a Celtic deity.

Furthermore, there is no evidence linking her to the Germanic seeress ‘Waluburg’, mentioned in a brief text on an ostracon from the 2nd Century CE.

The book “Illustrated Lexicon of Germanic Deities” can be ordered at:

https://blackwells.co.uk/bookshop/product/Illustrated-Lexicon-of-Germanic-Deities-by-Goos-Gunivortus/9783756855971